Despite efforts, minorities lag in representation in Sacramento leadership positions

Some Sacramento business leaders believe the region is so focused on downtown development that a critical issue is being neglected: diversity in the C-suite.

“People are just trying to seize the moment to catapult Sacramento to the next level,” said Sacramento Metro Chamber of Commerce CEO Peter Tateishi. “We’re all racing, but we’re not making a priority of demographic issues.”

Barry Broome has a similar view. He arrived last year as CEO of the Greater Sacramento Area Economic Council after decades spent on economic development in Arizona and Ohio. He said he thinks the region may be complacent about executive diversity.

Despite California’s reputation for broad-mindedness, “When I raise the question of young people and people of color in leadership, people are almost dumbfounded by the question,” Broome said. “On the East Coast, people take a much more comprehensive view and have conversations about it.”

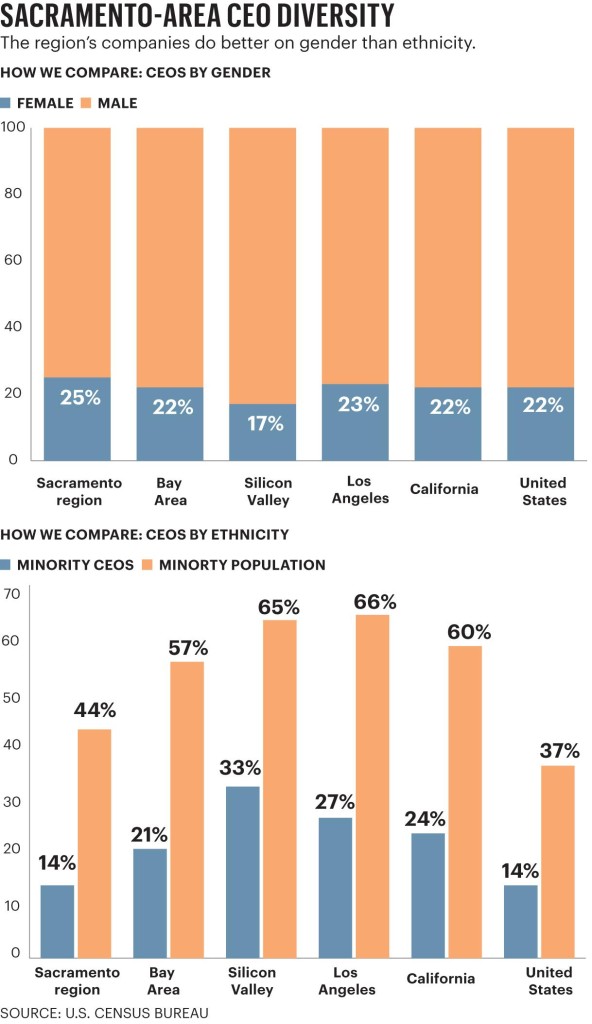

Part of the problem is that facts are in short supply. There’s no definitive measure of diversity in the region’s business leadership. U.S. Census figures, however, suggest that women fare better than minorities in winning leadership roles here.

Estimates for 2006 through 2010, the latest available, found that women held 25 percent of about 7,000 private, public and nonprofit CEO positions in the four-county region. Across California and the nation, 22 percent was the norm.

About 14 percent of Sacramento-area CEOs were ethnic minorities. That’s no better than the national rate, even though Sacramento’s population is far more diverse. And it’s a far lower percentage than in other California metro areas.

Government may play a role

One factor is that Sacramento’s dominant industry, government, may disproportionately attract minorities, said Scott Syphax, CEO of the Nehemiah Corp. He also is founder of the Nehemiah Emerging Leaders Program for young people from underrepresented backgrounds.

“Many talented minorities felt they had a better shot in government,” he said. In order to change that way of thinking, the community needs to promote entrepreneurship for people of color, he said.

“Because of the government mentality in this town, we talk a lot about preparing college students to get jobs, and we’re not really speaking to young people enough about creating the corporations that they can lead,” he said.

Another factor may be the makeup of the Sacramento corporate base, said Pat Fong Kushida, CEO of the Sacramento Asian-Pacific Chamber of Commerce. She wonders if the picture would be different if the region had more young companies.

“Millennials are color-blind,” she said. “If you look at new companies, you see diversity in them. Maybe that’s part of the issue — we don’t have a lot of startups.”

Definition evolves

One challenge of promoting diversity is that conversations can lead to affirmative action. That’s not what many young business leaders are looking for.

“I would rather you don’t recruit me because of my skin tone. I would rather you recruit me based on the skills I bring,” said Michael Marion, executive director of Drexel University Sacramento and a 2011 graduate of the Nehemiah program. “It’s a matter of these corporations taking the extra effort to really look.”

Similarly, it can be dangerous to judge companies for their lack of diversity among managers, said Tateishi. That’s because employers need to fill those slots with the most qualified people.

“You don’t want to just establish a quota,” he said.

Many supporters of greater executive diversity also favor a broad definition of the term.

“We’ve been talking about race too long,” said Stephen Nichols, vice president of diversity engagement at the Maryland-based National School Public Relations Association.

Nichols, who is African American and who graduated from the first class of Nehemiah in 2009, said it would be shortsighted to focus diversity efforts exclusively on people of color.

“The new face of diversity is not what people expect it to be. You have transgender coming up, people with disabilities.”

“Nobody is saying (black people) have arrived and the work is done,” Nichols continued. “But, at the same time, we have to make (diversity efforts) applicable for every community.”

Building the pipeline

That’s where professional development programs come in. In order to increase Sacramento’s corporate diversity, people of color and other underrepresented candidates need to advance into corporate hiring pools. Companies also need to know where to look to find these candidates.

Sacramento has many programs that aim to catapult people into leadership positions. The Sacramento Black Chamber provides entry-level business skills and mentoring to high school and community college students through its Young Entrepreneurs Academy.

Catalyst, a program from the Sacramento Asian-Pacific Chamber of Commerce, takes a group of 20 young professionals through a nine-month course that includes mentorship training and requires graduates to join a nonprofit board.

The Nehemiah Emerging Leaders Program follows a similar formula, though supporters call it a more rigorous program that teaches young people about the inner workings of the local private and public sector. It also introduces them to major local decision-makers.

Many graduates have found the program helps them move up. Nehemiah, which tracks the progress of graduates, cites several examples of success.

Yen Marshall, who joined the 2012-2013 class as a developer at AT&T, now is an area director of the company’s external affairs office. Nicole Howard, who was a supply-chain supervisor at the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, now is the agency’s chief customer officer. And Tamiko Moon, who was a regional sales manager with VSP when she joined the program, now is director of strategic marketing at Shriners Hospitals for Children Northern California.

Many of the fellows who have gone through Nehemiah were rising stars when they entered the program, so it’s difficult to link their current professional success as proof that the program is working. But Marion of Drexel said the exposure to leadership was critical to his success.

“Programs like Nehemiah put you in a room and a conversation where otherwise you would not have access,” he said.

A priority for some

Doni Blumenstock, Nehemiah’s program director, says businesses “haven’t been knocking our door down” to nominate employees. “We may be more of a well-kept secret as far as the business community is concerned.”

But some organizations in the region are well recognized for making leadership diversity a priority. Nearly everyone interviewed for this article mentioned the same four as being at the forefront: VSP Global, SAFE Credit Union, Kaiser Permanente and the Sacramento Municipal Utility District.

Gary King, chief workforce officer at SMUD, said the utility is “cognizant of how we look” in part because it is a public agency. SMUD is not where it needs to be on the diversity spectrum, he said, “but it is an area that we give focus.”

Over a decade ago, when Time magazine declared Sacramento as the nation’s most diverse metro area, SMUD created an “office of inclusion” to help the company better reflect its customer base, King said.

And participants in a two-year volunteer program study best practices in corporate diversity and pursue a project the second year to implement them. For example, one cohort created a strategic plan to improve diversity at every satellite office.

Promoting ethnic diversity in the workplace does not come without challenges, said Rod Githens, assistant dean at the Gladys L. Benerd School of Education at the Sacramento campus of University of the Pacific.

Studies show that productivity can actually drop when workplaces become more diverse, Githens said, because employees from different backgrounds may not mesh well. To avoid this, employers can promote affinity groups, or groups within a company of people from similar backgrounds or interest areas. This allows people to gain comfort and confidence in the office, and those groups can help recruit new employees that come from similar backgrounds.

If managers take steps to promote inclusivity, they can be rewarded with greater innovation because of a diverse set of perspectives.

“If you hire a bunch of Stanford MBAs that are all from elite schools and have higher economic status, their life experience won’t allow them to see things from the same point of view as others,” Githens said. “If you are trying to bring in creative ideas, and everyone has the same experience, you won’t be able to do that.”

Source: Sacramento Business Journal